Thursday, May 26, 2011

Easter 5 - Fr. Damian Feeney

Homily given by Fr Damian Feeney, vice principal of St Stephen's House, on Easter V, 22nd May 2011. (Readings: Acts vii.55-60, 1 Peter ii.2-10, John xiv.1-14)

**

Like living stones, let yourselves be built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. (1 Peter 2.5)

Strictly Come Dancing isn’t what it was. For those who are of less than a certain age, it is based on a late night BBC programme which ran in the 1970’s called ‘Come Dancing’ which was a regional ballroom dancing competition. It ran from 1949 to 1998. In the realm of Latin Dancing, there was simply no-one to rival Home Counties South, who were invariably represented by the Penge Latin Formation Team, coached by the legendary Frank and Peggy Spencer; quite simply, they carried all before them, to the presumable chagrin of the other regions. So well drilled were they, so rehearsed to the inch, that they achieved astonishing success.

One of the most important things about the experience of residential training is that we are formed, as it were, in formation. In our case this doesn’t mean that we all act, or move, or speak, or even dress the same way – we aren’t being trained to be clones. It does mean that our formation has several dimensions, from the forming of personal and individual habits and virtues which prefigure the grace of ordination to the important understanding that our journeys to ordination and beyond do not take place in isolation. We cannot be solitary living stones, and our journeying is connected by a complex network of relationships which extend beyond our year group, beyond this House, and even beyond the boundaries of living and dying. Living in formation is part of what it means to belong to the church catholic, as our experiences of God in Christ are mediated to us through the church local and universal. Such a way of life implies that what affects one affects all: whilst your eyes are necessarily fixed on the day when you will join another community – that of the parishes to which you are called, and where another type of living in formation is on the cards – there is no denying that the social habits of our life here will stay with us, and form the way in which we undertake our patterns of living in other places.

One of you said to me the other day that he believed the House to be the kind of place which you grew to dislike while you were here, but demonstrated a huge depth of loyalty and love to thereafter. All of us know by now that as ordinands, no theological college is a place in which to tarry. Many of our anecdotes after ordination will doubtless consist in the things that happened while we were here, and – please be gentle with us – the staff who taught us. But to live, to pray and to learn in community is vital, for by so doing we are seeking the very heart and example of the Holy Trinity, a community of love and mutual concern that models a different way of being to a church which sees training in such a way as too expensive, and to the world around us which struggles to define and live out what it means to be community at all.

The challenge, then, is to live as those who, as the church, mediate Christ to one another. By living in formation here we undertake a responsibility not only for our own training and shaping, but for that of each other. Our actions, words and examples, for good or ill, shape the thinking and attitudes of individual members of this whole community. And how important that is, in a college where not everyone we meet has a ‘church’ background, or understands our ways of speaking and doing things.

If I may stretch the analogy, living stones depend on one another to stay in position. In a dry stone wall, the dislodging of one stone brings about a collapse of the stones around it, because each relies on the mass, inertia and shape of the others to keep the wall stable. Each of us is called to occupy a different place within the edifice of the church, and for different reasons, and we do so by responding as faithfully as we can to God’s call which, we pray, locates us where we are needed. And, if we are Living Stones, then we must let ourselves be shaped by God into the kind of structure he wants, rather than building large personal edifices of our own called ‘careers’.

There will inevitably be times when we are called to question this – whether we are in the right place, doing the right thing – and there will be times when we do not understand why it is we have been placed where we have until much later on (if at all). If we become angry or frustrated in our situations, and on reflection recognize that those feelings are but a reflection of the community in which we serve, then that should act as an incentive to us; not to justify a superficial desire to ‘bale out’ when the going gets tough, but rather to seek the grace of perseverance and endurance, in our prayer life, our abandonment to the will of God, and to tasks which being in that situation implies. Seek the help, seek the support, of your parishes, your families, your networks, the groups to which you belong. But remind yourself of the consequences of pulling the stone out of the wall, as far greater damage may ensue.

More than this, we need to learn to trust processes, and that God’s grace makes up whatever is lacking in the church through human frailty. All of you who have accepted title parishes and incumbents up and down the country will be aware of a certain sense of risk. It is necessarily a process in which you, the parish and the diocese are called into decision with a relative lack of knowledge. If nothing else, we have to believe that the process that has led us to this place, the point in our lives, has been a grace-filled one, and that through the processes of the church we are being located to a place where we are called to be. There is also a sense in which the very act of trusting, of risking, places us in a situation where we have to rely on God’s resources rather than our own. And his grace is sufficient. ‘Like living stones, let yourselves be built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ’.

Friday, May 20, 2011

Monday Reflection - Simon Maddison

This homily was given by Simon Maddison, a first year ordinand, at Evening Prayer on Monday 16th May 2011;

I have based my homily on the readings we have just had (Exodus 32:1-14 & Luke 2:41-end), so I’m going to start with a brief recap...

From Genesis we heard, how when Moses had left the Israelites to go up Mount Sinai, they lost their way somewhat! Having being left to their own devices they forced Aaron in to making a golden calf that they could then worship, and subsequently, but for the intervention of Moses on their behalf, would have been destroyed by God.

In Luke’s Gospel we heard how Mary and Joseph “lost” Jesus while on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Presumably they would have been preoccupied with packing things away for their return trip, making sure they had got everything before they set off, and had just assumed that Jesus was with friends travelling with them.

I am sure we can all sympathise; I usually remember what it is I have forgotten just as I drive on to the main road, forcing me to go all the way to the next roundabout just to go back and get it...

Similarly they are a day into the journey when they realise that Jesus is not with them, and are forced to go back to look for him, eventually finding him teaching in the temple.

Now these two stories are quite different in their content, but I think there is a common theme about the nature of faith, and our relationship with God.

In both cases the people involved lose their focus, whether it’s because they feel abandoned, or because they just have too many other things going on. However their responses are quite different.

When Moses is away longer than expected, the Israelites just give up on him and more importantly the God that he represents, seeking to replace him with something of their own making, and very nearly bringing about their own destruction in the process.

So unlike Mary and Joseph, who on discovering Jesus missing, instantly begin searching for him, going back to Jerusalem and not giving up until they find him three days later.

The situations may be different but I am sure we have all had similar experiences to these, when God can seem quite distant, or the concerns of our day to day life drown out everything else; after all we have, books to read and essays to write...

But I think what these stories show us is that it is not God that moves or changes, it’s us and our circumstances, and no matter how busy or disconnected we may feel from time to time, we can’t replace God with something else, we need to go back looking for him, remembering he is only ever a prayer away.

And so let us pray...

Let nothing disturb you,

Nothing affright you;

All things are passing,

God never changes.

Patient endurance

Attains unto all things;

Who God possesses

In nothing is wanting:

Alone God suffices.

St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582).

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Oxford Artsweek at St. Stephen's House

Oxford Artsweek at St. Stephen's House

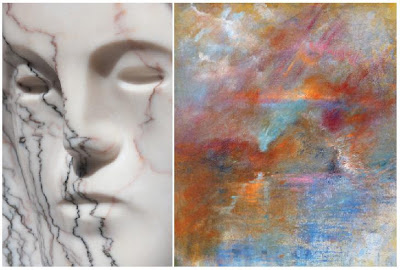

Paul Vanstone Sculptures

Nick Maitland Paintings

Private view by invitation

Sunday 22 May 2011

5.00pm to 7.00pm

(R.S.V.P. to assistantbursar@ssho.ox.ac.uk / 01865 613 504)

Public view

Monday 23 May 2011 - Monday 30 May 2011

**

Monday & Tuesday 2-5pm

Wednesdays 12-4pm

and

Thursday-Friday 2-5pm

**

St. Stephen's House

16 Marston Street

Oxford OX4 1JX

Paul Vanstone Sculptures

Nick Maitland Paintings

Private view by invitation

Sunday 22 May 2011

5.00pm to 7.00pm

(R.S.V.P. to assistantbursar@ssho.ox.ac.uk / 01865 613 504)

Public view

Monday 23 May 2011 - Monday 30 May 2011

**

Monday & Tuesday 2-5pm

Wednesdays 12-4pm

and

Thursday-Friday 2-5pm

**

St. Stephen's House

16 Marston Street

Oxford OX4 1JX

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Monday Reflection - Joanna Moffett-Levy

This homily was given by Joanna Moffett-Levy , a final year ordinand, at Evening Prayer on Monday 9th May 2011;

There is a theme in today's readings and that theme is awe, awe at God's overwhelming greatness. First, in Psalm 29 'the voice of God is over the waters, the God of Glory thunders.' God's voice shatters the greatest of the trees and makes the wilderness shake.

In the reading from Exodus, God prepared Moses and the people of Israel for the giving of the law on Mount Sinai. The people needed to be pure to receive God's words and the mountain was so holy that no creature might touch it. Thunder and lightning, thick cloud and smoke were all around when the people met at the foot of the mountain. God's presence was like the loud blast of a trumpet, like an earthquake, like a violent storm. In the next chapter we will hear that they asked Moses to speak to God for them – they were afraid that if God spoke directly to them they would die.

And lastly, we heard Luke's account of the message given by the angel to Zechariah, husband of Elizabeth and father of John the Baptist, a message that came to him as he served God in the sanctuary. Imagine the shock when he looked up to see the angel standing by the altar of incense. Gabriel was there bringing the message from the place where he stands in the presence of God. Zechariah questioned the message, mildly, and as a result was rendered silent; his silence lasted until the circumcision of John in the Temple.

We are shown in these readings that God's power is overwhelming, like a terrifying natural phenomenon; we human beings cannot look at God, cannot survive in God's presence – we need a go-between like Moses or the angel Gabriel. Our response, our right response, is awe and fear.

The contrast for us this week is between this God who thunders and the God in Christ of the road to Emmaus. The Lord is present with the two disciples and walks along the road with them and is with them at the table as they eat. They may not recognise him at first, but they see him face to face.

Can we keep these things in balance? I think that we do need both but it is not easy. We may find the intimacy easier than the awe. We don't get a lot of practice at awe, I think, here in a city, away from whirlwinds and floods and earthquakes. But our fellow Christians in New Zealand certainly have. The theologian in residence at Christ Church Cathedral, New Zealand, Revd. Lynda Patterson, struggling with where to look for God in the destruction, wrote this recently.

"the earthquake was not an act of God. It was just the earth doing what it does. Under our feet there are two unimaginably vast slabs of rock floating in the tides of a ball of liquid iron. They grind on slowly, as they have done for millions of years, and where they rub together the earth is pushed up at the seams into mountains, or swallowed up in vast trenches. Sometimes the slabs move, stick and then move again as they did for us. Into all this impermanence, we are born and set up camp for the briefest of periods. But that's not the end of the story. Behind this globe of molten rock, there is a God who designed it all and put it in place. There is a God who knows just how breakable we are and how much it hurts, because that God has been here and walked about, laughed and wept and died and rose to life again here among us."

So this week I am going to keep trying to get a glimpse of the God who we know in the breaking of bread and who fills the dark spaces between the stars.

Monday, May 9, 2011

House Lecture - Dr Colin Podmore

All are warmly invited to

The House Lecture

presented by

Dr Colin Podmore

Clerk to the Synod Central Secretariat

Communion and Consultation:

The Anglican Communion and its "Instruments of Unity"

Thursday 12th May 4.30pm

The Curatin Room

St. Stephen's House, Oxford

16 Marston Street, Oxford, OX4 1JX

01865 613500

enquiries@ssho.ox.ac.uk

[map]

The House Lecture

presented by

Dr Colin Podmore

Clerk to the Synod Central Secretariat

Communion and Consultation:

The Anglican Communion and its "Instruments of Unity"

Thursday 12th May 4.30pm

The Curatin Room

St. Stephen's House, Oxford

16 Marston Street, Oxford, OX4 1JX

01865 613500

enquiries@ssho.ox.ac.uk

[map]

***

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

St. George's Day - Fr. Damian Feeney

Homily given by Fr Damian Feeney, vice principal of St Stephen's House, on St. George's Day, 2 May 2011. (Readings: Rev xii.7-12 2 Tim ii: 3-13: John xv.18-21.)

As a small and rather pious boy, I recall a conversation with my mother which she has doubtless forgotten, (and will therefore deny!) but which set a train of thought going that continues to this day. In a quest for rather premature careers advice, I asked her, after the manner of Doris Day, what I should become. Rather splendidly, she advised me that I should become a saint. She painted an attractive picture of sainthood, and heaven, which has never quite left me; nor has her parting shot, which betrayed the all-too human struggle beneath her lofty sentiments. ‘Be a saint, but don’t be a martyr’ she said. Martyrs had a hard time of it, because they had to die to win the crown, and that was perhaps not calculated to be an appealing job description for a six-year old child. I think with the passing of the years, both of us would see the flaws in that statement. But it was good enough for a precocious boy. Of course, the call of the Christian life for us all is a call to holiness, to virtue, to self-renunciation, and to the rule of love. Saints don’t theorise about sanctity, but rather live it, expound upon it, proclaim it. Often the sacrifices saints are called to make are as a result of doing these things well – of shaping virtuous lives and souls in a less than perfect world. Those who have undergone martyrdom have in some sense experienced the same consequence of God-centred living that Jesus did – words, thoughts and actions considered too dangerous, too subversive, for the places and times in which they occurred.

There are three words which haunt the preacher who turns to hagiography for inspiration. They are the words ‘little is known’. This opening to a sentence, or paragraph, about a saint may make us groan; it is certainly the case for St. George, venerated as a martyr and swathed in popular legend. Importantly, George’s tradition and cult has been remarkable, both in the history of the church and in his position as Patron of this land. Indeed, it may well be that his lack of local association led to an easing of his passage towards being our Patron Saint. Not merely in this country, but throughout Western Europe and indeed in the writings of Islam, George is revered as an heroic figure who was faithful, courageous, and who endured to death.

A Martyr, of course, is a supreme witness to the truth of the faith, even to death. He or she endures death through fortitude, offering their very being into God’s hands to dispose as He will. It is the ultimate recognition that our life is ‘not I, but Christ in me’ and that all we are and have is given to us through the Grace and generosity of God. It is an act of profound love and trust, intimately related to our crucified saviour, as the need to witness to the truth of the faith supercedes and transcends our earthly being.

We live in an age when martyrdom is misunderstood. A 12 year old walks in to a regimental barracks in Mardan, Pakistan, and detonates the bomb which brings to an end not only his own life, but that of 31 others; all on the promise of glorious martyrdom. That isn’t martyrdom – it’s murderous suicide. However we may feel about it, there will be those who will see Osama Bin Laden’s death earlier today as a martyrdom. This casts a pall over the very notion of martyrdom in the world, for there can be nothing that is holy about willing and bringing about the murder of thousands of people. None of this can be of a piece with seeking and witnessing to the truth; it is rather a gross perversion of it.

Alongside all this – and given that patron saints give us cause to examine our country – we are forced to examine the ‘witness to truth’ as it is represented in our own day. In many ways, this is not an easy time to be ordained: and being ordained places us, ontologically and visibly, as those who will be the focus for questioning, scrutiny and even attack within a wider society which is being taught to mistrust the church. Bearing witness to the truth of Christ in such a context is a challenge requiring of us great patience, charity and virtue. There may even be times when such witness, combined with our own human frailty, may break us – but God’s grace is sufficient, and we heal, and grow, and orient ourselves once again to the pursuit of grace-filled, truthful living which is God’s desire for us, and such moments of crisis can act as a catalyst for a more grounded and loving response in pastoral ministry. I delighted in Pope Benedict’s description yesterday of the final days of his predecessor, Blessed John Paul the Second. He said,

Then too, there was his witness in suffering: the Lord gradually stripped him of everything, yet he remained ever a "rock", as Christ desired. His profound humility, grounded in close union with Christ, enabled him to continue to lead the Church and to give to the world a message which became all the more eloquent as his physical strength declined. In this way he lived out in an extraordinary way the vocation of every priest and bishop to become completely one with Jesus, whom he daily receives and offers in the Church .**

Whether called to Martyrdom or not, the call to witness to the truth of Jesus Christ is the flame which burns at the very centre of His call in our lives. To love our country – to be patriotic - does not merely mean being an unconditional supporter of every aspect of our national life. Rather, it means being prepared to express that love in labour for that peace, justice, and right ordering of society’s affairs which are expressions of the Kingdom of God. May the prayers of St. George assist all our labours of love with his fervent prayers, and may we in our turn seek to witness to the truth of Jesus Christ, wherever that truth may lead us.

** http://www.romereports.com/palio/Pope-Benedicts-homily-at-John-Paul-IIs-beatification-english-4033.html

DAMIAN FEENEY

Vice Principal, St. Stephen’s House

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Book Launch

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)